Do I contradict myself? Very well, then, I contradict myself; I am large — I contain multitudes – Walt Whitman

Before turning west to El Paso and the far reaches of Texas, route 62 drops south from New Mexico, hugging an eastern edge of Guadalupe Mountains and the looming El Capitan. As if lost, the highway leads back into New Mexico and Las Cruces, before smoothly tracing a path westward into the sweeping vistas of Arizona. Chiricahua and Dos Cabezas Peak keep me company as a warm cinder wind gathers on the desert floor. To the south, Apache Peak fades from view, hidden by dustbin colored clouds. As I turn north toward Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain bathes shamelessly in sunlight, lording over the land of shrugging giants.

Saguaro National Park is bisected by Tuscon, Arizona. To the east is Rincon Mountain District, 67,000 acres of high desert. Virtually inaccessible, except on foot or horseback, Rincon District rests in the Sonoran Desert, gradually sloping up to meet the Rincon Mountains. To the west, separated by thirty miles of Tucson and its tentacled suburbs, the 24,000 acre Tucson Mountain District sits low and dry. Both Districts share the Sonoran Desert, but at differing elevations. Each giving life to its own ecosystem of plants and animals.

Carnegiea gigantea. A forest of saguaro cacti fills the Sonoran Desert

Cactus Forest Loop is eight miles of unpaved road into the skin of the Rincon District. Twisting and dipping, the dusty road leads past some of the tallest saguaro in the park. Reaching heights of 30-40 feet, with outstretched or upturned arms of 10-15 feet, these regal plants lend themselves to countless interpretations. Some seem to be saying, ‘I have no idea.’ Others, ‘I give up.’ I saw one that looked exactly like a third base coach waving a runner home. Several looked depressed, arms at their side. A few shorter ones had a smile on their face. Then of course there are the monolithics. Interpret them at your own peril.

The Desert Ecology Trail extends outward from the loop, leading into a dazzling display of life supporting plants, illustrating the role saguaros play in creating a wildly diverse, perfectly disguised ecosystem where nothing is wasted or without purpose. The Gila woodpecker and gilded flickers shelter and raise families in saguaros. Other birds compete for apartments in the suguaro, where winter temperatures are 20 degrees warmer inside the cactus wall. In summer months, saguaro fruit ripens, with each sugary pulp containing as many as 2,000 seeds. Foxes, squirrels, javelinas and a host of other birds and animals feast on the seeds before redepositing them into the soil as nutrients. Long-nosed bats and honeybees feed on the saguaro’s spring blossoms. I could start singing ‘The Circle of Life’, but I won’t. I am humming it.

When I spoke to ranger Barb, she said they are still discovering saguaro with unique top-growths, known as Crested Saguaro. “We have people who actively hunt for one of a kind saguaro. They are obsessed.” Well, Barb, I hate to brag, but here you go

ith elevations ranging from 2,670 to 8,666 Rincon District also contains six biotic communities. Desert scrub, which I am hiking through at the moment, desert grassland, which I am approaching, oak woodland, which I can see up ahead, pine-oak woodland, pine forest and mixed conifer. Because of the varying elevation, plant and animal diversity follows. Black bear, Arizona mountain king snake (it’s difficult to just type the name), Mexican spotted owl, mountain lions and white-tailed deer, call the Rincon district home. It is comforting to know that at lower elevations the most dangerous animal I’m likely to run across in the daylight is a crazed jack-rabbit. And as if on cue, there goes a large jack-rabbit. Light as a feather through the yellow grass, without so much as a hello. For the record, theses are not your cuddly small bunny rabbits. They look more like a cross between the Easter bunny and a kangaroo. I’m taking no chances. I’ve seen far too many Bug Bunny cartoons. And just like that, another muted grey jack-rabbit scurries into the brush.

I wasn’t quick enough to get a shot of the jack-rabbit, but somehow this lizard stood still long enough for me to get a shot. He also gave me the stink eye. It’s a reoccurring theme.

I spent five days in the Oro Valley that lies between the eastern and western districts of Saguaro. Five days to get caught up on writing and other business obligations. Between driving, hiking, photography, posting and logistical planning, the days get eaten away. At one point I looked up and had been to three parks without writing about them. Simply no time. So I gathered up my notes and literature from the various parks and headed to the Oro Valley library. I was going to carve out time.

Culling through the hundreds of photos I take at each park, is a time consuming task. I try to narrow them down to about a dozen, but many times fail. I want to try and convey what I’m seeing and the right photos are critical. And I’m picky, but don’t tell anyone. Writing a piece takes about 8-12 hours, so at least one secluded day. Everything that is stored in my notes and head, have to find a place on the page and I am well aware that each piece can not be a novel unto itself. So I carefully (not necessarily skillfully) create sentences and photos and place them on a page. It’s what I love to do. But it does take time

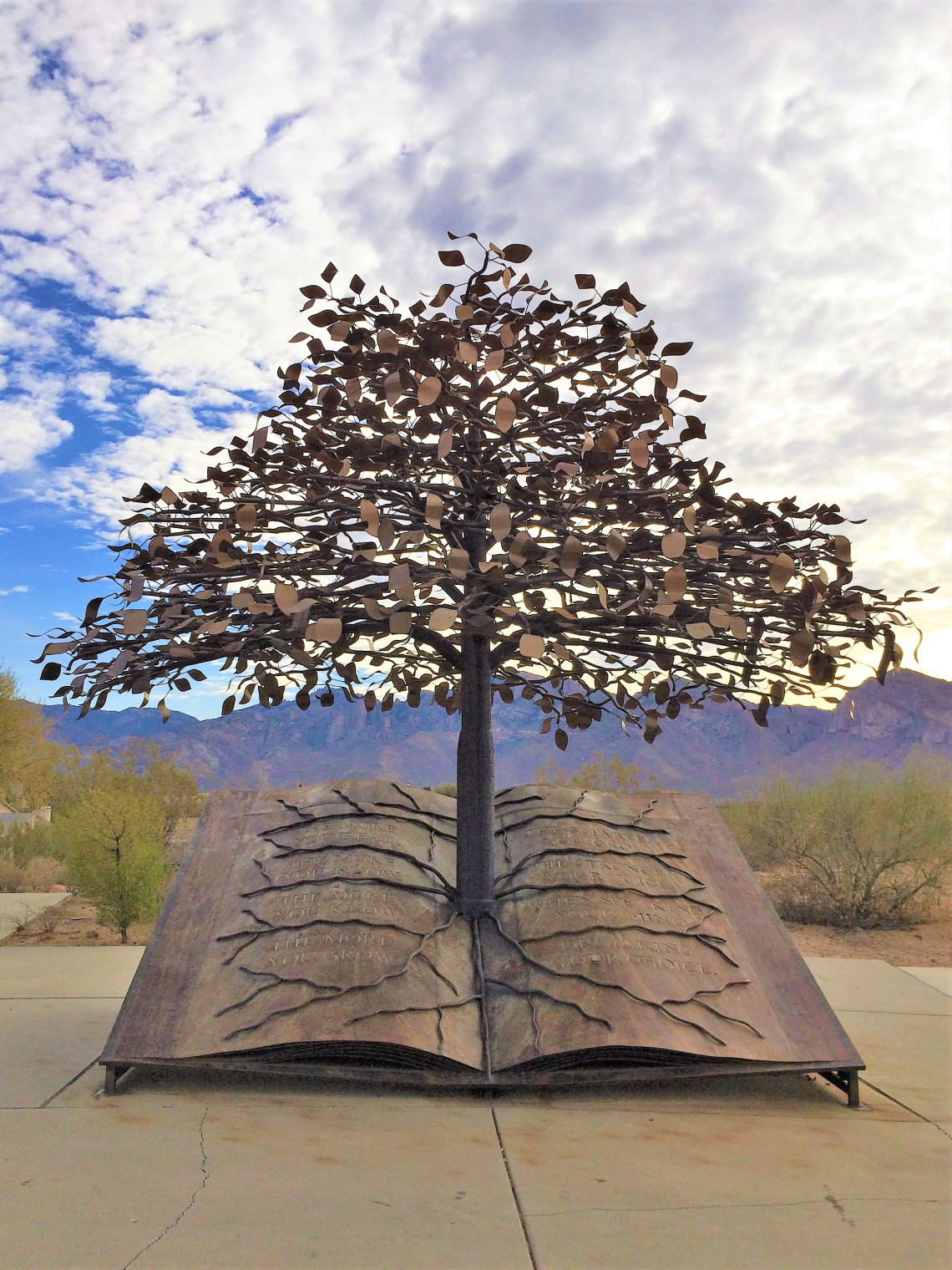

Beautiful metal sculpture outside the Oro Valley library – my home for several days.

Cutting into Baja Loop Drive in the Tuscon Western District of the park, Signal Hill Trail leads past a series of shelters built by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the 1930’s. Small structures of stone with wooden cross-joints, they look as if they were finished yesterday. As in many of our National Parks, evidence of the Corps works are present throughout. In Saguaro, another example lies only two miles away on Valley View Trail, where the trail itself was cut out of the desert floor by the Corps. Our parks as we know them today, do not exist without the labor and skill of the Civilian Conservation Corps. They were paid $1 a day and given food and shelter. For more than a few, this represented a chance to regain a level of dignity, lost during the depression. A change to contribute to something larger than themselves. I am constantly amazed by their works

Civilian Conservation Corps built this shelter in 1934. Note to self: The best drive of this trip was on a road built by the CCC. Nothing else has come close

Just beyond the stone shelters, the trail begins to climb a series of stone steps before warning me that I am in an active rattlesnake area and curving behind a large outcropping of rocks. At the peak of Signal Hill, etched in stone by Hohokam Indians over 800 years ago, sits a jumble of rocks with primitive chalk-like markings. Archaeologists believe the symbols may have signified territorial claims or clan migrations. Others believe some of the symbols, chipped through a brown patina of iron-magnesium oxide, are personal works of art or ‘artistic whimsy’. I thought of them as Snapchat postings that have lasted 800 years.

An amazing display of ancient Hohocam art in the middle of the Sonoran Desert.

Leading archaeologists believe this says, ‘Keep your Scottish Terrier on a leash. He keeps chasing my horse with horns.’ The figure on the right apparently has 3 legs

Camping on the westward edge of Mountain Time Zone, it begins to get dark by 5:00. Soon the moon lifts its round face above the Santa Catalina Mountains, darkening the soaring 9,159 ft Mt. Lemmon. Lying on my back, I wait patiently as stars begin to emerge, individually hand placed on black felt. As my eyes adjust to the darkness, constellations materialize. Cassiopeia, Ursa Minor. Perseus emerges above low hanging Neptune. Thousands of pinhole lights begin to blink on. Then millions. A child’s nightlight made of punctured tin and spun bedside. Small red lights float silently across the sky at 30,000 feet. Movement of a single white speck draws my attention to another muted traveler and I begin to trace a satellite’s eastward glide. Off in the distance, wolves begin their nightly conversations. Howls, punctuated by staccato yips, followed by low murmurs. A black night’s soundtrack. I close my eyes and once again think about how lucky I am.

The beautiful, green skinned Paloverde tree.

A close-up of the mighty, prickly saguaro, which can live well over 150 years.

I found this fellow rather stylish, but lonely. Not sure why he is so isolated. It’s not like having six arms is odd in this part of the world.

As voted by the ‘Desert Inhabitants Club,’ the 2018 award for best dreadlocks once again goes to Irving ‘3 head’ Fitzman

This cactus was about 40 feet tall. He had rather short arms, was a bachelor and considered odd by his neighbors.

God damn it kids. One more time. Patty, picked a pack of pickled peppers. Now get it right.

NOTE: For more information on Saguaro National Park and all the National Parks and to help with trip planning, download the free Chimani app to your smart phone to easily navigate your way around the park, with or without cell phone service